KEY CONCEPTS

The Western U.S. continues to see large increases in wildfire activity due to rising temperatures, buildups of pine needles and other potential fuel on forest floors, and urban growth into forested areas. More wildfire activity means more smoke pollution.

Wildfire smoke has been connected to a long list of health problems, including asthma and heart attacks. Scientists recently discovered that exposure to smoke waves increases influenza risks the following winter, and experts fear the same may hold true for COVID.

Other types of air pollution, including truck exhaust and chemical irritants like tear gas, increase susceptibility to respiratory infections and other health problems, including COVID.

Driven by warming temperatures and other issues, like forest management decisions and urban growth, Western wildfire seasons are starting earlier and burning with greater intensity on average. Rising temperatures are contributing to droughts and causing snowpacks to melt earlier, compounding wildfire threats. With the fiercening of flames has come a blotting of the skies—smoke waves have been smothering communities from quiet foothill towns to major metropolitan centers, forcing cancellations of local events, driving vulnerable residents indoors and exacerbating existing health risks. The rise in smoke levels during warmer months is undermining improvements in air quality driven by the regulations on pollution from fossil fuel use and other sources.

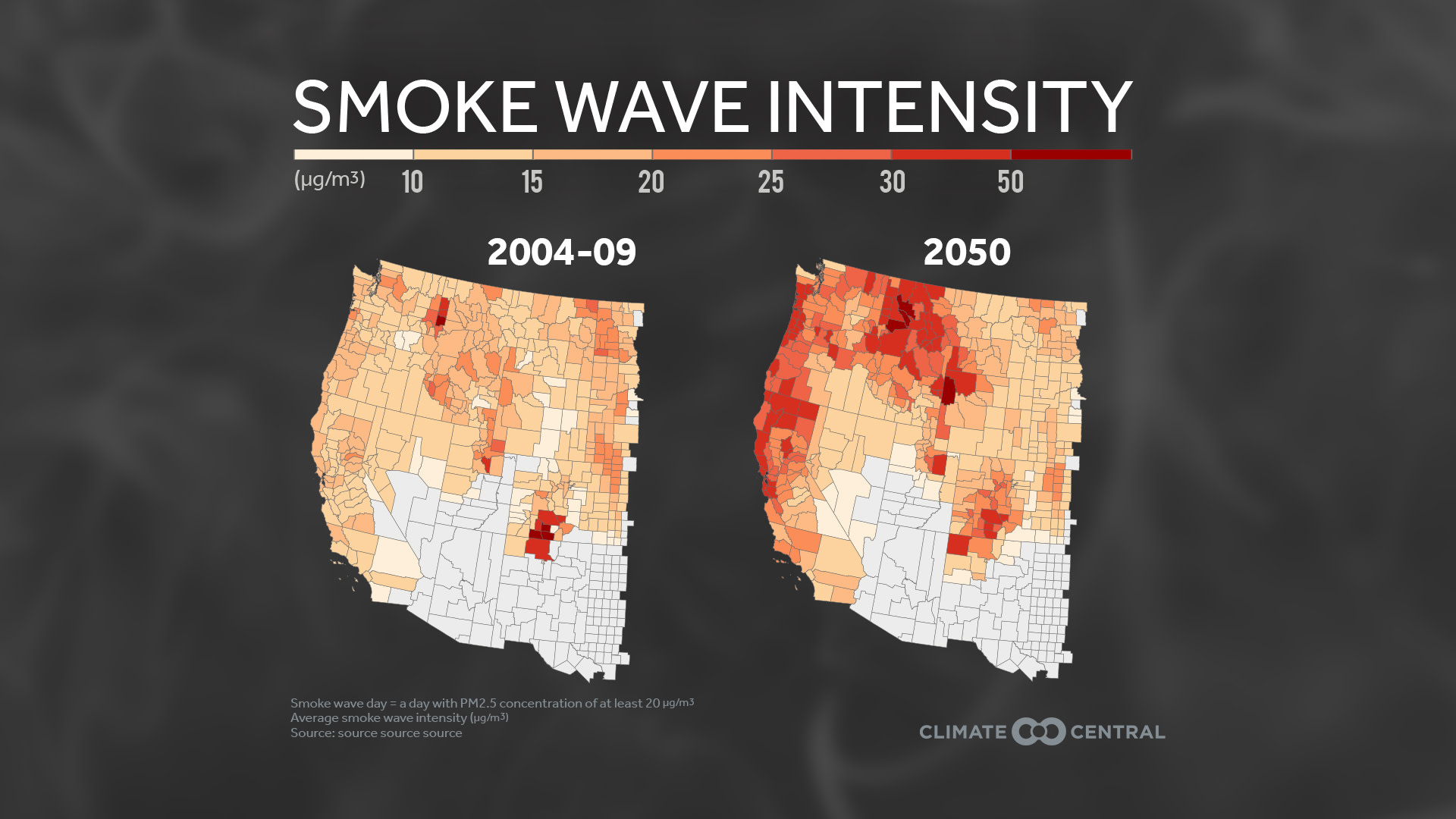

Scientists project the intensification of smoke waves to continue as temperatures continue to increase due to heat-trapping pollution. Forests and grasslands dry out as temperatures increase, fueling larger and more frequent blazes.

Forest management practices also influence wildfire seasons. The use of prescribed burns are one of the tools available to land managers, in which crews ignite and manage low-intensity fires on forest floors to reduce fuel, but they are used inconsistently nationwide.

Wildfires can affect ozone pollution levels and release broad arrays of dangerous chemicals into the atmosphere, but it’s the tiniest of the particles that usually cause the biggest threats—PM2.5, which refers to particles or droplets in the air that are two and a half microns or less in width. These particles can lodge deep in the lungs and even enter the bloodstream, increasing risks of heart attack, diabetes and many other ailments.

Lung health is important for surviving COVID. Exposure to particulate matter from wildfire smoke could increase risks of death from coronavirus. So, too, does the use of tear gas by police forces during demonstrations. Research involving soldiers exposed to high concentrations of tear gas during combat training concluded that exposure increased risks of developing acute respiratory infections, with risks greatest at the highest concentrations.

Exposure to pollution from tailpipes, refineries and other industrial sources has been shown to increase deaths from COVID. That puts Americans who live with polluted air, many of them low-income and people of color with limited access to healthcare, at greater risks of dying from the disease.

Wildfire smoke can trigger and exacerbate a long list of health problems including asthma attacks, headaches and runny noses. And health impacts can linger long after smoke from a fire has cleared. Research from University of Montana scientists showed how particulate matter from wildfires increased the risk of influenza months later.

For Climate Central’s coverage of how wildfire smoke and tear gas could affect COVID suffering this year, read and listen to our partnership story with KQED.

POTENTIAL LOCAL STORY ANGLES

How are local government and communities preparing for wildfire season?

The COVID-19 pandemic is presenting novel challenges for wildfire preparations and responses this summer. Watch an online workshop put together by Climate Central and the International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM) to prepare journalists and meteorologists for reporting on local emergency planning efforts during wildfires. You can find out about your state’s plans for wildfire preparation by contacting your local Emergency Management Agencies.

Firefighter tactics

Local firefighting agencies can describe how they are shifting tactics this year to protect firefighters from COVID spread. The National Interagency Fire Center has overseen the drafting of plans for nine geographic regions to help guide effective wildfire responses during the pandemic.

Public health

Residents with asthma and other lung conditions may be willing to share their concerns about COVID and wildfire smoke—and how they plan to protect themselves. Nurses can be helpful sources for gauging the wellbeing of a community.

Everything you need to know about wildfire season

The National Significant Wildland Fire Potential Outlook is produced by the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) in Boise, Idaho.

Sci-Line has a fact sheet and experts ready to talk about wildfires, and Climate Signals has materials on climate change and wildfires.

Firewise USA® is a voluntary program that provides a framework to help neighbors get organized, find direction, and take action to make homes and communities more fire-resistant.

The U.S. Drought Monitor map is released every Thursday, showing parts of the U.S. that are in varying levels of drought, from abnormally dry to exceptional.

AirNow, a partnership of multiple government agencies, has a number of publications on wildfire smoke and air quality, and a wildfire and smoke tracking map.

EXPERTS TO INTERVIEW

Erin Landguth, Associate Professor, School of Public and Community Health Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula. Research interests: computational ecology and the relationships between biological processes, environment, and climate with population patterns. erin.landguth@mso.umt.edu

Colleen Reid, Assistant Professor of Geography, University of Colorado, Boulder. Research interests: health impacts of exposure to air pollution from wildfires, extreme heat events, and proximity to urban vegetation. Colleen.Reid@colorado.edu

Madhavi Dandu, Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. Research interests: human rights and global public health. madhavi.dandu@ucsf.edu

Loretta Mickley, Senior Research Fellow, Atmospheric Chemistry Modeling Group at Harvard University. Research interests: chemistry-climate interactions in the troposphere. mickley@fas.harvard.edu

Josué Medellín-Azuara, Acting Associate Professor of Environmental Engineering at the University of California, Merced. Research interests: climate change adaptation, large-scale hydro-economic models for water supply and agricultural, environmental and urban water use. jmedellin-azuara@ucmerced.edu (Available for interviews in English and Spanish.)

METHODOLOGY

A smoke wave refers to at least two consecutive days of wildfire-specific PM2.5 at a concentration of at least 20 micrograms per cubic meter. Changes in average western smoke wave intensity from the recent past (2004-2009) to the future (2050) were obtained from Liu et al. (2016) using CMIP3 models.