KEY CONCEPTS

Heat is the #1 weather-related killer in the U.S., and climate change is making bouts of deadly heat longer and more frequent. As our climate continues to change we’re likely to be exposed to more heat than we’re used to, increasing the risk of heat-related illness.

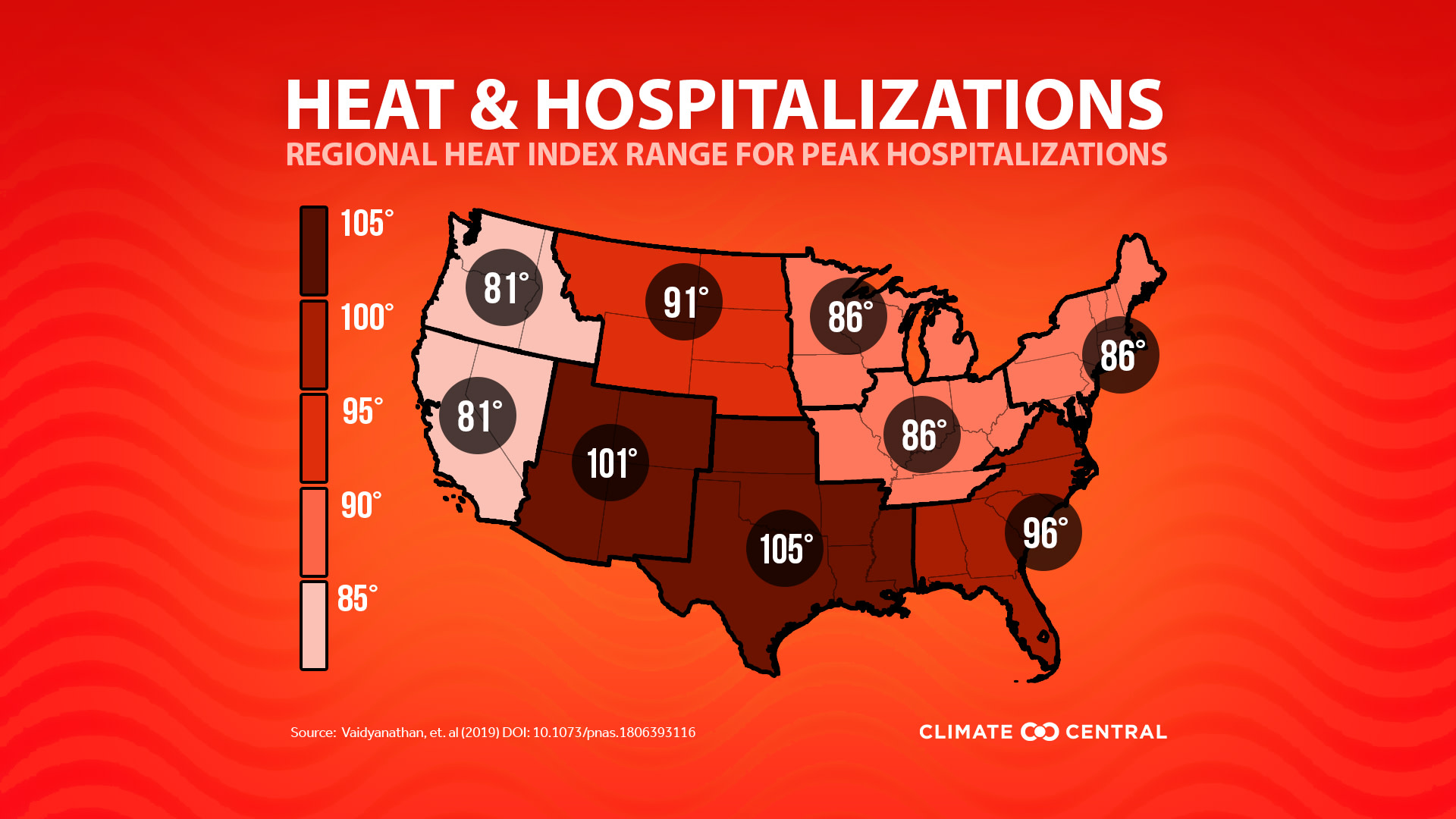

A 2019 study looked at how hospitalization visits rise in response to heat index values. Researchers found that heat-related hospitalizations begin at lower heat values in traditionally cooler regions (Northwest, West, and Northeast) compared to the South and Southeast.

NOAA determines that a heat index of 90 or above presents a risk of serious, heat-related illnesses. Climate Central’s analysis of these dangerously hot days found that the number of uncomfortable and potentially dangerous days is rising throughout the country. The increase is especially strong in the Southeast and Texas, with many locations experiencing over two additional weeks of dangerous heat compared to 1970.

Heat affects people unequally. Higher risk categories for heat illness include children and people over 65, as well as those with chronic health conditions such as obesity, heart disease, and diabetes. Outdoor laborers and athletes training outside are also at greater risk. Low income communities that may lack air conditioning or greenspaces are also at higher risk.

Heat is the #1 weather-related killer in the U.S., and climate change is making bouts of deadly heat longer and more frequent. The Pacific Northwest, a region with historically milder summers, experienced all-time record-toppling temperatures, such as 108℉ in Seattle and 116℉ in Portland. As our climate continues to warm we’re experiencing longer periods of intense heat, even in places that we don’t think of as hot, increasing the risk of heat-related illness.

A 2019 study examined hospitalizations from extreme heat. The study examined cases of heat-related hospitalizations and the heat index at which these cases start to show up in the hospital waiting room. The researchers found that this association varied widely by region, with the Northwest, West and Northeast all being susceptible to heat illness at lower heat indices, while heat-related hospitalizations in the South, Southwest, and Southeast showed up at higher heat index values.

People in historically cooler regions may be less acclimatized to heat, and lack the infrastructure to cope with it. According to the 2019 American Housing Survey, Seattle, WA is the least air-conditioned city of the top 15 metro areas surveyed. And while the southern United States appears to be better adapted to extreme heat, even these areas are getting hotter with climate change.

NOAA determines a heat index of 90 or above to present risk of illnesses such as heat stroke, muscle cramps and heat exhaustion. Climate Central’s analysis of these dangerously hot days found that the 25 locations with the largest increases in average number of days with a dangerously high heat index were located in the Southeast and Texas—all with over two additional weeks of dangerous heat compared to 1970. Of the 239 stations analyzed across the country, 70% (167) recorded an increase of 3 or more days of dangerous heat, and 46% (109) recorded an increase of a week or more.

Much of the country has struggled with extreme heat over the past two weeks. However, it affects us all unequally. Higher risk categories for heat illness include children, people over 65, and those with chronic health conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. Increased exposure to heat puts those who work outside (e.g. construction workers, landscapers, farm laborers) at greater risk, too. Lower income communities are often more exposed to heat either due to historic redlining, or prohibitive costs of air conditioning.

PICTURING HEAT

Images are an important part of the extreme heat story and should help to illustrate the seriousness of the risk to human health. Here are a few compelling examples:

WORLD WEATHER ATTRIBUTION

The World Weather Attribution (WWA) group investigated how much the recent Pacific Northwest heat wave was attributable to climate change. Based on the highest temperatures during the event, they found that the heatwave was 150 times more likely and about 3.6°F (2°C) hotter as a result of climate change.

POTENTIAL LOCAL STORY ANGLES

What measures are local officials taking to protect people from extreme heat?

The EPA maintains a Community Actions Database of measures that communities are taking to mitigate the heat island effect in their area. Emergency management can help reduce risk in vulnerable communities against the impacts of climate change. FEMA has a dedicated page with tools, data, and resources to learn more. For state specific emergency management information, search your state here on the USA.gov site. To learn more about projections for vulnerable populations, check out the stories and projects from ISeeChange.

How do local authorities assess if a heat advisory should be issued?

A 2019 study from the National Academies of Science found that heat-related hospitalizations may, in some regions, begin to occur before heat advisory messages are issued by the local National Weather Service (NWS) offices. You can contact your local NWS office to find out more about how they keep your community informed about excessive heat.

Which neighborhoods in your area are more susceptible to excessive heat?

Check out the Future Heat and Vulnerability Map created by the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) that assigns a vulnerability score to each county across the U.S. based on race, income, and other parameters.

LOCAL EXPERTS

The SciLine service, 500 Women Scientists or the press offices of local universities may be able to connect you with local scientists who have expertise on extreme heat and climate change. The American Association of State Climatologists is a professional scientific organization composed of all 50 state climatologists. The American Red Cross opened cooling shelters in the Pacific Northwest, as well as Chicago and Detroit. You can find open Red Cross shelters here, and contact information for your local Red Cross location.

NATIONAL EXPERTS

Dr. Ambarish Vaidyanathan, Climate and Health Program, Division of Environmental Health Science and Practice, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Email: rishv@cdc.gov

Rob Dale, Meteorologist and Emergency Planner, Ingham County (MI) Office of Homeland Security & Emergency Management, International Association of Emergency Managers - Climate and Weather Caucus. rdale@ingham.org

Dr. Cheryl Holder, Internal Medicine, Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, Inclusivity, and Community Initiatives at Florida International University's Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine (FIU HWCOM); Co-Chair, Florida Clinicians for Climate Action (FCCA); and Co-Chair, Miami-Dade County Heat-Health Task Force. To schedule an interview, contact Melissa Baldwin at FCCAStaff@Ms2ch.org or 727-743-3778

METHODOLOGY

The daily maximum temperature and minimum relative humidity was assessed from 1979 to 2020 at the 239 contiguous U.S. stations typically analyzed by Climate Central, using the gridMET modeled dataset and based on the findings of Dahl et al. 2019. Heat index temperatures were calculated using the National Weather Service’s heat index algorithms. The change in the number of 90°F+ is based on linear regression. Local graphics were not produced for Eureka and Monterey, California or Flagstaff, Arizona due to a lack of days in which the calculated daily heat index met or exceeded 90°F during the study period.