KEY CONCEPTS

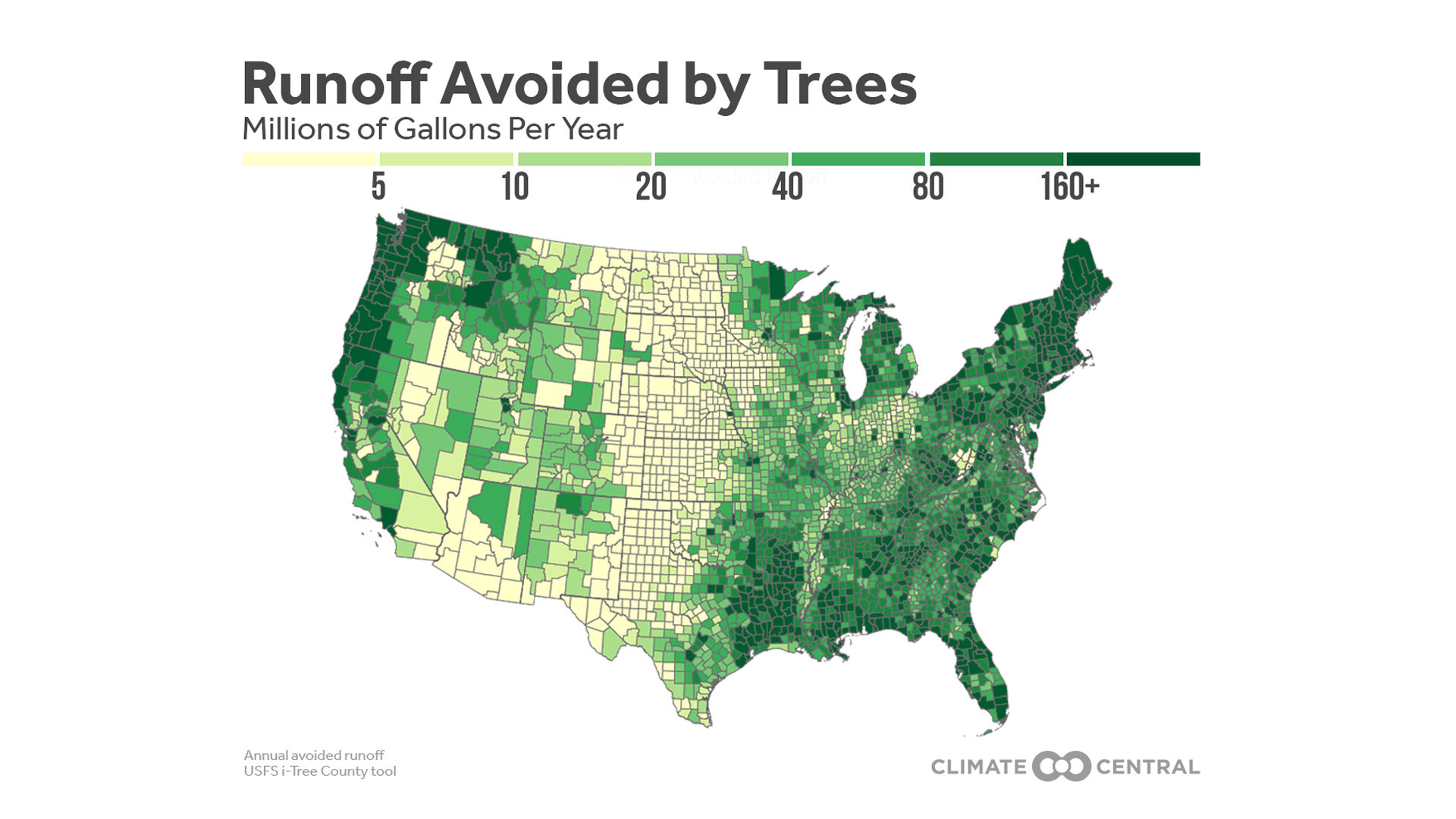

Trees divert and slow down rainwater runoff, reduce erosion, and create more permeable soils, saving nearly 400 billion gallons of stormwater runoff in the continental United States each year.

Climate change is leading to increased precipitation and extreme downpours. This year, the U.S. experienced its wettest past 12 months on record—three months in a row.

The U.S. Forest Service has an online tool that allows users to assess urban and rural forest benefits.

Trees help control stormwater by intercepting rainfall, promoting the evaporation of water with their leaf canopy, and absorbing water from the ground through their roots. Climate change is leading to heavier downpours and U.S. cities are seeing their wettest days get even wetter, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest.

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

Trees’ ability to reduce stormwater runoff is most visible in highly developed areas that are prone to high runoff rates.

Harris, Texas (home to Houston) leads the Forest Service’s county data, followed by Middlesex, Mass. (near Boston), Allegheny, Penn. (home to Pittsburgh), and Cook, Ill. (home to Chicago).

Results are similar when aggregated by media market, with New York, Atlanta, and Boston ranking highest in avoided stormwater. Trees also save more stormwater in rainier regions, including the Gulf Coast and the Pacific Northwest.

Trees limit climate change impacts in multiple ways:

U.S. forests can act as a “carbon sink,” offsetting 10 to 20 percent of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions each year.

U.S. trees remove more than 35 billion pounds of air pollutants every year, preventing more than half a million annual cases of acute respiratory symptoms.

In urban areas, trees’ cooling effect reduces U.S. energy bills by more than $5 billion each year.

POTENTIAL STORY ANGLES

How much are the trees near you creating positive environmental impacts?

The i-Tree County online tool can quantify a number of benefits of your local trees, including avoided runoff, carbon sequestration, and equivalent vehicle emissions reduced. Users can select among several i-Tree tools to analyze tree canopy, land cover, and other basic demographic information.

Looking for information about which trees to plant locally?

The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas, Austin, has a searchable native plants database and lists of recommended tree species by state. And the i-Tree species tool enables users to find appropriate tree species based on potential environmental benefits and geographic area.

How is climate change impacting forests in your neck of the woods?

The U.S. Forest Service maintains Treesearch, an online database of free, peer-reviewed research. Filter for articles by topics such as “climate change,” and then search your region or state. Read about overall climate change and ecological disturbances on U.S. forests in the 2018 National Climate Assessment.

LOCAL INTERVIEW IDEAS

The SciLine service,500 Women Scientists or the press offices of local universities may be able to connect you with local scientists who are knowledgeable about how climate change is affecting trees and forest areas in your state.

The Association of Nature Center Administrators’ interactive map can help you locate a local nature center that provides environmental education or stewardship.

Connect with forestry experts near you through the regional offices of the U.S. Forest Service.And ForestryUSA lists state and municipal organizations on their Forestry Community site.

NATIONAL INTERVIEW SUGGESTIONS

Adam Berland

Ball State University

Assistant Professor of Geography

HOW WE GOT THE DATA

2010 county-level data is plotted from the U.S. Forest Service i-Tree County Tool. i-Tree uses canopy area, local weather data, and precipitation models (Hirabayashi 2015) to estimate annual avoided runoff. Data is not normalized to account for the differing sizes of counties. Local graphics aggregate the county data into Nielsen Designated Market Areas (DMAs), as described in last year’s release. Average annual county-level rainfall was calculated from 1970-2018 using the NOAA/NCEI nClimDiv dataset. Complete data was only available within the contiguous U.S.